Irène de Palacio

4 déc. 2025

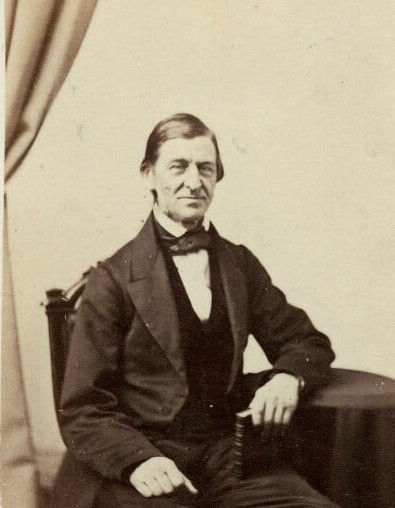

[From : Edward W. Emerson ; Emerson in Concord (1889)]

1838.

"The American artist who would carve a wood-god and who was familiar with the forest in Maine, where enormous fallen pine-trees "cumber the forest floor", where huge mosses depending from the trees, and the mass of the timber give a savage and haggard strength to the grove, would produce a very different statue from the sculptor who only knew a European woodland, — the tasteful Greek, for example.

It seems as if we owed to literature certain impressions concerning nature which nature did not justify. By Latin and English Poetry, I was born and bred in an oratorio of praises of nature, flowers, birds and mountains, sun and moon, and now I find I know nothing of any of these fine things, that I have conversed with the merest surface and show of them all ; and of their essence or of their history know nothing. Now furthermore I melancholy discover that nobody, — that not these chanting poets themselves , know anything sincere of these handsome natures they so commended ; that they contented themselves with the passing chirp of a bird or saw his spread wing in the sun as he fluttered by, they saw one morning or two in their lives, and listlessly looked at sunsets and repeated idly these few glimpses in their song.

But if I go into the forest, I find all new and undescribed ; nothing has been told me. The

screaming of wild geese was never heard ; the thin note of the titmouse and his bold ignoring of the bystander ; the fall of the flies that patter on the leaves like rain ; the angry hiss of some bird that crepitated at me yesterday ; the formation of turpentine, and indeed any vegetation and animation, any and all are alike undescribed . Every man that goes into the woods seems to be the first man that ever went into a wood. His sensations and his world are new. You really think that nothing can be said about morning and evening, and the

fact is, morning and evening have not yet begun to be described. When I see them I am not reminded of these Homeric or Miltonic or Shakspearian or Chaucerian pictures, but I feel a pain of an alien world, or I am cheered with the moist, warm, glittering, budding and melodious hour that takes down the narrow walls of my soul and extends its pulsation and life to the very horizon. That is Morning ; to cease for a bright hour to be a prisoner of this sickly body and to become as large as the World. ”

June, 1841.

"The rock seemed good to me. I think we can never afford to part with Matter. How dear and beautiful it is to us. As water to our thirst so is this rock to our eyes and hands and feet... What refreshment, what health, what magic affinity, ever an old friend, ever like a dear friend or brother when we chat affectedly with strangers comes in this honest face, whilst we prattle with men, and takes a grave liberty with us and shames us out of our nonsense.

The flowers lately, especially when I see for the first time this season an old acquaintance, — a gerardia, a lespedeza, — have much to say on Life and Death. 'You have much discussion, they seem to say, on Immortality. Here it is : here are we who have spoken nothing on the matter.' And as I have looked from this lofty rock lately, our human life seemed very short beside this ever-renewing race of trees. 'Your life,' they say, 'is but a few spinnings of this top. Forever the forest germinates ; forever our solemn strength renews its knots and nodes and leaf-buds and radicles.'

Grass and trees have no individuals as man counts individuality. The continuance of their race is Immortality ; the continuance of ours is not. So they triumph over us, and when we seek to answer or to say something, the good tree holds out a bunch of green leaves in your face, or the woodbine five graceful fingers, and looks so stupid-beautiful, so innocent of all argument, that our mouths are stopped and Nature has the last word.

I cannot tell why I should feel myself such a stranger in nature. I am a tangent to their sphere, and do not lie level with this beauty. And yet the dictate of the hour is to forget all I have mislearned ; to cease from man, and to cast myself into the vast mould of nature."

July, 1856.

"Returned from Pigeon Cove, where we have made acquaintance with the sea, for seven days. 'T is a noble friendly power, and seemed to say to me, Why so late and slow to come to me ? Am I not here always, thy proper summer home ? Is not my voice thy needful music ; my breath thy healthful climate in the heats ; my touch thy cure ? Was ever building like my terraces ? Was ever couch so magnificent as mine ?

Lie down on my warm ledges and learn that a very little hut is all you need. I have made this architecture superfluous, and it is paltry beside mine . Here are twenty Romes and Ninevehs and Karnacs in ruins together, obelisk and pyramid and Giants' Causeway, here they all are, prostrate or half-piled. And behold the sea, the opaline, plentiful and strong, yet beautiful as the rose or the rainbow, full of food , nourisher of men, purger of the world, creating a sweet climate, and in its unchangeable ebb and flow, and in its beauty at a few furlongs, giving a hint of that which changes not, and is perfect."